Life, the Universe and Everything: a question to which the answer is 42… apparently. Today, I'm only going to tackle two thirds of that question, and all based on what we know so far. I'd advise you to strap in.

Astronomers like to joke that their job is simply to "look up". But if you’ve ever stood outside on a clear night, with little or no light pollution and "looked up" you've likely been staggered by all you can see. You might be able to spot a planet, the pole star, name some constellations, but you will be left struck by the immensity of it all - and how much you don't know.

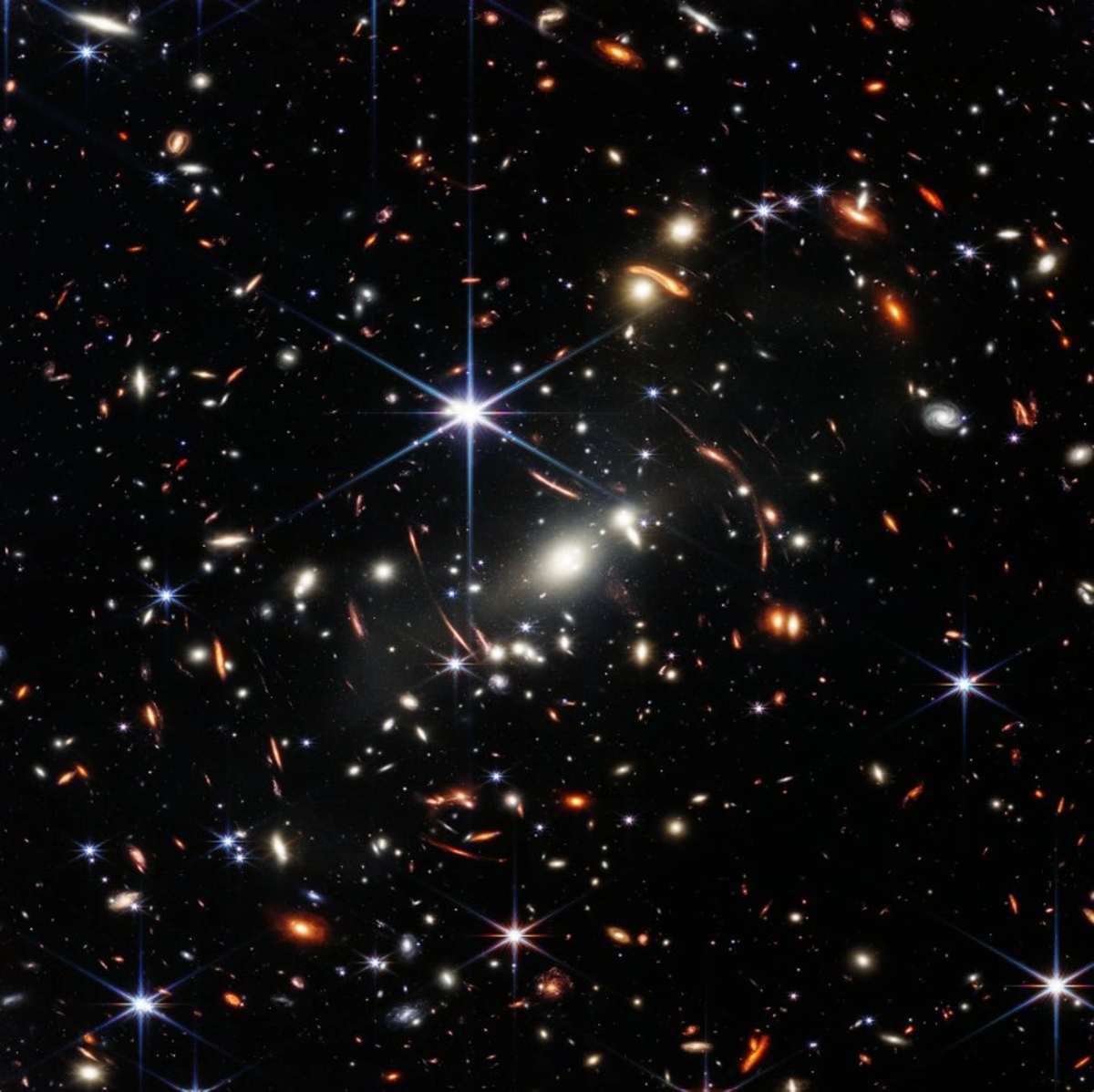

So how do we start to make sense of the universe? The best way to begin is by patiently observing all that we can. Astronomers are the archivists of the universe, cataloguing what the cosmos has chosen to reveal to our ever improving instruments. Stars, galaxies, nebulae, quasars, rogue planets, supernova remnants—each object is logged, measured, compared, and placed into an ever‑expanding cosmic inventory. The universe is vast, but astronomy is built on the belief that if enough observations are made, patterns will emerge.

And indeed, they do.

However, observing the universe is only half the challenge. The other half is working out where everything actually is - and where it's going. Space does not come with convenient signposts or distance markers. When you look at a star, you have no intuitive sense of whether it is ten light‑years away or ten thousand - or if it's receding or approaching.

Measuring distances to local stars and objects is achievable by geometric techniques. Parallax is the apparent shift in an object's position when viewed from different locations. The Earth orbits the sun at a distance of about 90 million miles and, at the opposite sides of its orbit, local stars appear to shift position. By measuring these subtle shifts, their distances can be calculated. But this only works for objects that are relatively close.

To estimate distance on an intergalactic scale astronomers rely on objects with a fixed, known brightness. The further away these “standard candles” are, the dimmer they appear. So if you know how bright they are supposed to be then you can use this to estimate distance. Some examples of these standard candles are close enough to be measured by parallax, allowing their brightness to be calibrated. This is then used to measure the distances of standard candles further away and, by inference, anything (relatively) close to them. Cepheid variable stars, which pulse with a rhythm tied to their luminosity, were the first great breakthrough. Later came Type 1a supernovae, exploding stars so uniformly bright that they can be seen across billions of light‑years.

As to movement, this uses the "Doppler effect". Picture an ambulance racing past you. As it approaches, the pitch of the siren rises; as it speeds away, the pitch drops. Light behaves in the same way.

How does it work? Imagine a steady stream of joggers approaching in a line, and imagine they all want to give you a high-five. If you were to walk towards them, as they jog towards you, those high-fives would come more quickly. Alternatively, if you were to back away, those high fives would happen more slowly. Sore hand aside, what you've experienced is a change in frequency of those high-fives. With sound, a frequency shift results in a change in pitch. With light, it results in a change in colour.

In astronomy, when an object is moving towards us, the light waves shift towards blue. If it's moving away, then they shift towards the red. By measuring the redshift or blueshift of an object with a known colour you can deduce not only if it is coming or going, but how fast.

It's when we started putting these distance and speed measurements together that the story takes a dramatic turn. Astronomers used these measurements to study how galaxies move and they found something deeply unsettling. Galaxies were spinning so fast that, by rights, they should have torn themselves apart. The visible matter—stars, gas, dust—simply didn’t provide enough gravitational glue to hold them together. Something unseen had to be contributing mass, something that exerted gravity but emitted no light. This invisible scaffolding became known as dark matter. If it sounds like a vague name, it's because it is, it's a label for a phenomenon we don’t' understand. And the more astronomers looked, the more dark matter they found. In fact, it sculpts the large‑scale structure of the universe - like an invisible cosmic web.

But the surprises didn’t stop there. When researchers used the Type 1a supernovae (which I mentioned earlier) to measure how the universe’s expansion had changed over billions of years, they expected to find that gravity was slowing everything down. Instead, they discovered the opposite. The expansion was accelerating, as if some mysterious force were pushing galaxies apart faster and faster. This repulsive influence was christened dark energy, another name that admits that we have no idea what it truly is.

The really astounding thing about dark matter and dark energy is that, if it exists, it makes up about ninety‑five percent of the universe. It is humbling to think that despite all we can see, the best we can currently do is speculate that it is dwarfed by what is invisible and untouchable.

Fortunately, science is not content to stop there. Recently, astronomers and cosmologists have started asking whether dark matter and dark energy are the only—or even the best—ways to explain what we see. Some suggest that our understanding of gravity might be incomplete, or that Einstein’s equations might be missing a footnote or two when applied to the entire universe. Others argue that the apparent acceleration could be a result of the assumptions baked into our observations.

It all leads to a big cosmic cliff-hanger. Where does it all end? Or does it? If dark energy keeps pushing, the universe will expand forever, growing forever colder and lonelier. But if dark energy changes over time, or if gravity has a surprise twist waiting in the wings, the expansion could slow, stop, or even reverse. In that case, everything might one day come crashing back together in a dramatic "big crunch"—that ends where everything began.

When it comes to science, there are literally no bigger questions than this. It's what makes astronomy so compelling, a field where every answer is an invitation to ask a better question.